Research

Our research focuses on macroevolution and paleobiology. The overarching goal of our lab is to understand how the genotype and phenotype interact across major evolutionary transitions during the history of life on earth. This is a central challenge in macroevolutionary theory that we tackle using evolutionary models to integrate a wide range of data, from fossils and paleogeography to genome sequencing.

Comparative Methods & Sci-Phy

We are interested in building models that combine data from extant and extinct species to study trait evolution and adaptation. Commonly known as phylogenetic (evolutionary) comparative methods, these tools have revitalized paleobiology and macroevolution research over the past 10 years. They are also one of the only tools used in every field of biology.

We are interested in building models that combine data from extant and extinct species to study trait evolution and adaptation. Commonly known as phylogenetic (evolutionary) comparative methods, these tools have revitalized paleobiology and macroevolution research over the past 10 years. They are also one of the only tools used in every field of biology.

In collaboration with Andrew Meade, we are currently developing Sci-Phy (Science with Phylogenies), a python library for phylogenetic comparative analysis. Sci-Phy can read in standard phylogenetic formats like nexus and Newick, as well as strings and sets. The library can be used to manipulate sets of trees (e.g., a Bayesian posterior samples) and comparative data, conduct simulations, and create advanced evolutionary models for categorical and numeric (continuous) data. It uses standard data science Python resources, like Pandas and NumPy, which can be scaled for high performance computing clusters using Dask. Our near-term goal is to build novel sequential and Hamiltonian Markov chain Monte Carlo algorithms into Sci-Phy using PyMc. We are designing SciPhy to be developed by the computational biology community managed through GitHub under an MIT license. We plan on an initial release in 2023.

The Sci-Phy logo above demonstrates a Bayesian MCMC sampler using PyMC3 and imcmc (5 chains – each chain is a different color, 8000 iterations).

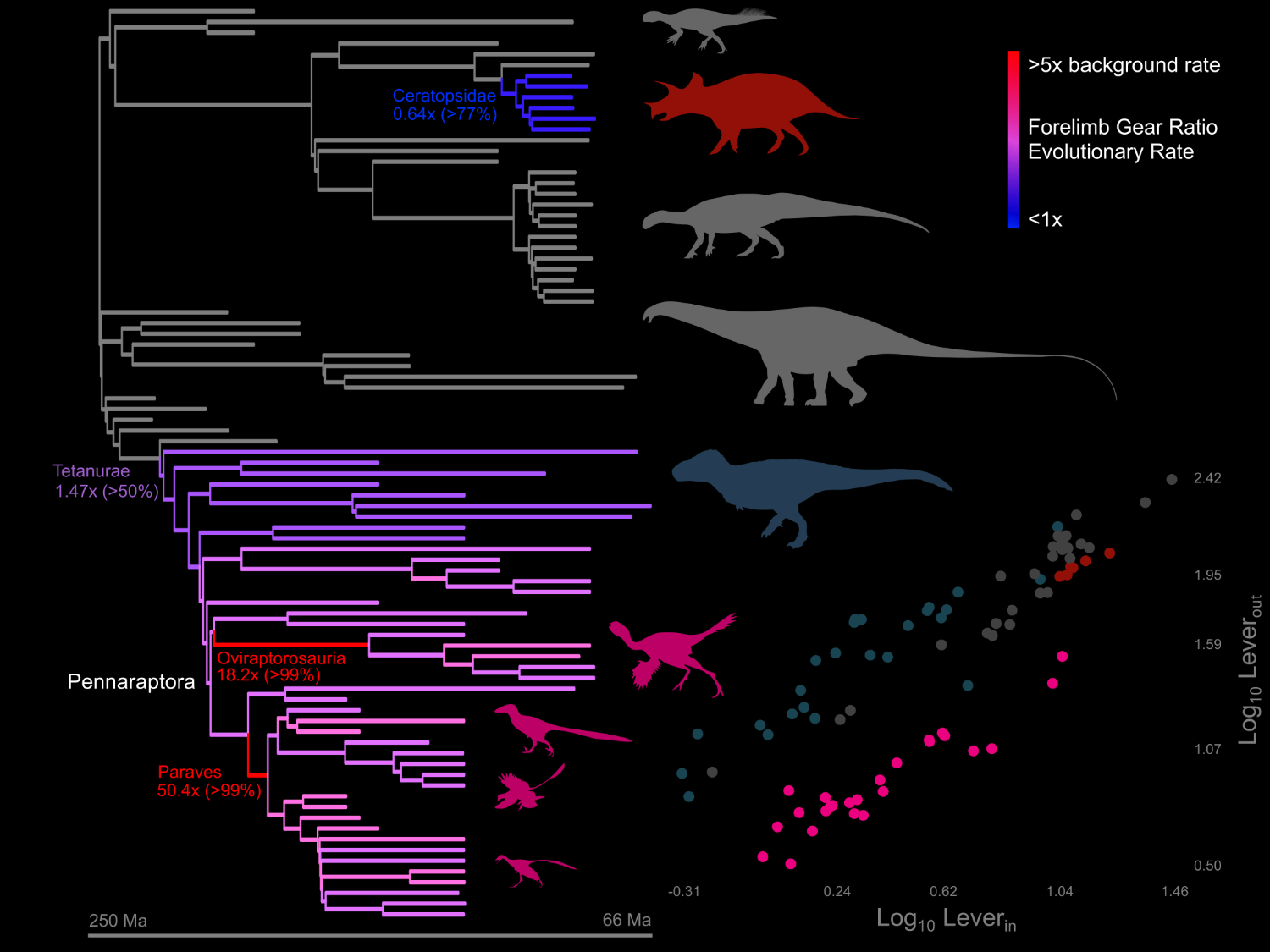

Macroevolutionary Ecomorphology

How do species adapt to new environmental challenges, ecological interactions, and balance internal constraints over geologic time? To address these questions, we are currently investigating the evolution of limb retraction by allowing the parameters of functional equations (lever arms) to evolve at differential rates across the Mesozoic dinosaur tree. Our results suggest that locomotor evolution is associated with speciation through dispersal or niche partitioning. This project builds on previous research showing that gigantic theropod dinosaurs had unique biomechanical spinal adaptations (Wilson et al., PLoS ONE, 2016) and evolved bony display structures (Gates, Organ, and Zanno, Nature Com., 2016) . We are currently interested in modeling heterochrony (evolution by shifts in growth rate and timing), which we plan to use to study human and hominoid evolution, as well as precocial running ability in vertebrate predators and prey.

The figure to the right shows an analysis of lever arm (gear ratio) evolution for the primary forelimb retractor muscles in dinosaurs. Warmer colors are increased, and cooler colors are decreased, evolutionary rates. Numbers indicate the median estimated rate shifts (posterior probability). Silhouette colors correspond to points in the lower-right plot. Note that despite being smaller, the arms of small, feathered dinosaurs provided more torque and evolved at faster rates. Despite orders-of-magnitude increases in body size, the lever arms of gigantic sauropods evolve gradually.

Paleobiology & Paleogenomics

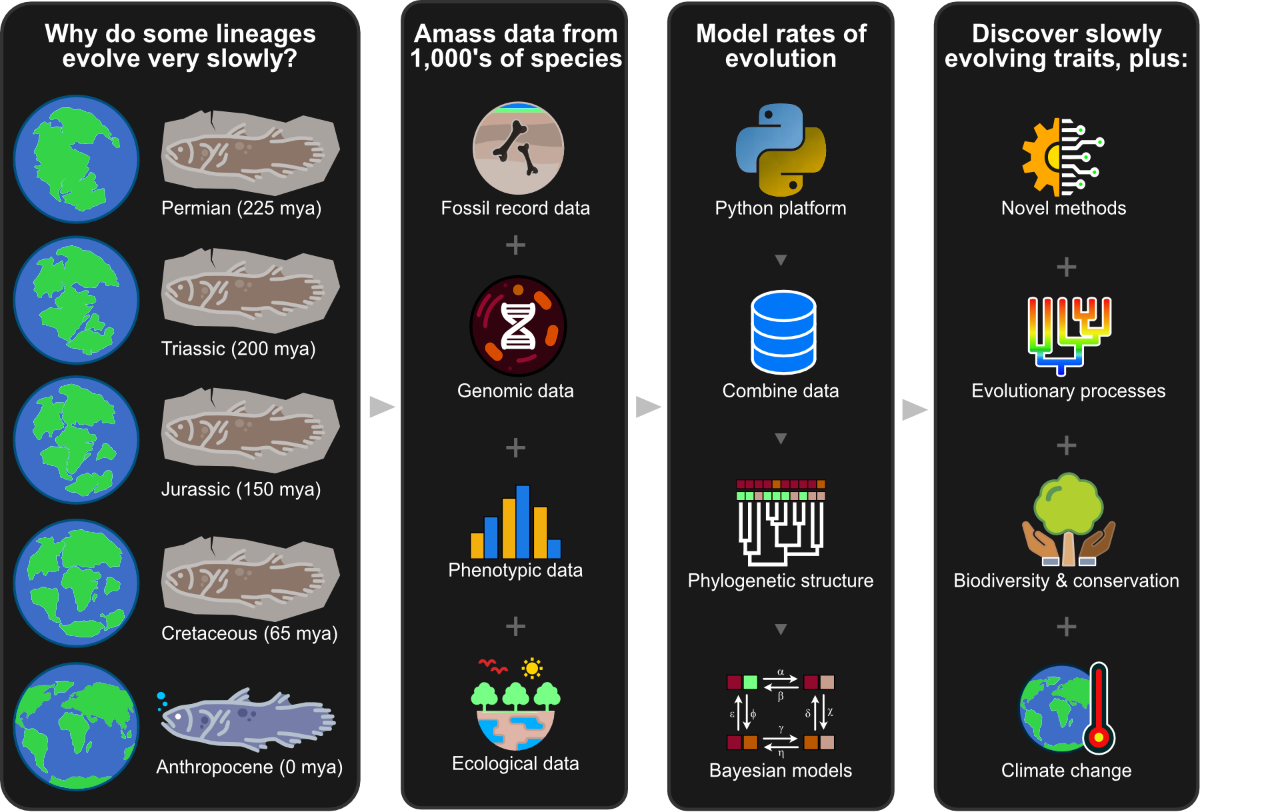

We are interested in the macroevolutionary processes that give rise to biological traits in extinct species, including genome biology and physiology. We pursue this by integrating molecular, genomic, and fossil data. For example, Chris’ work on the coelacanth genome revealed genetic adaptations in the urea cycle that allowed the water-to-land transition in vertebrates roughly 375 mya, consistent with fossil evidence (Amemiya et al., Nature 2013). Bone innervation was also crucial for the vertebrate diaspora onto land. It is essential in regulating bone growth, metabolism, and the perception of touch and pain, yet we know virtually nothing of bone innervation outside humans. We are currently developing a comparative study of bone innervation using micro-CT scans of bone from extant species and fossil vertebrates. Lastly, we are currently developing a project focused on “living fossils” that will shed light on why some lineages evolve so slowly. This follows recent work Chris did on the slowly evolving genome of the tuatara, a ‘living fossil’ reptile endemic to New Zealand (Gemmel et al., Nature 2020).

The figure above shows a graphical abstract for our Living Fossils project. Why do some lineages evolve very slowly (1st panel on the left)? We can answer this by integrating data from paleontology, genomics, and ecology (2nd panel). Bayesian models combine these data using computational platforms in Python (3rd panel). We expect to develop novel models and discover traits associated with evolutionary stasis, as well as evolutionary processes relevant to biodiversity and climate change (4th panel).

Student Participation

Students are welcome in our lab – no experience needed. You can learn the fundamentals of research on exciting topics like evolution, paleobiology, dinosaurs, physiology, and genomics. You will have opportunities to become proficient in data science tools like Python, R, and computer modeling, which are in high demand across academia and industry. You can expect to be supported along a gradual progression of responsibility, starting with small, semester-length projects that focus on fundamental technical skills, knowledge, and research culture. And if you are dedicated and have grit, you could contribute to scientific publications. If this sounds interesting, drop an email to Chris.